In the latest installment of Viznomics, Marc discusses how to get the gig and the flawed model of ‘Pay to Play’.

Previously, I hinted that I think the tech world doesn’t get the music ecosystem when writing about decentralised tension. In that post, I also pointed to an article I wrote about our rationale behind #HowWeListen. The post highlighted that the tech world is much better at sharing knowledge.

Music and tech comparisons are effective, in my mind. I have felt for a long time that while both sides actively (and rightly so) criticise each other, they have a lot more in common than they are willing to admit.

The music and tech comparisons I make are not unique though. Cherie Hu is even writing a book about the parallels between music careers and tech entrepreneurship. Cherie is a smart woman with a statistics degree from Harvard. If she is going in the same direction then I must be on the right track.

VCs (venture capitalists) are often critical of the music industry’s licensing system. Their view is that it is backwards and restrictive. Tech start-ups blame labels for streaming services’ low payouts to artists. Ironically enough, however, the VC model operates much in the same way. VCs offer upfront cash in exchange for a piece of future success, sometimes on very onerous terms. Antidilution provisions such as the “full ratchet” are great examples of this.

While I am sure there are many other comparisons, one specific similarity comes to mind.

murderecords

There were no “music business” courses or colleges back when I started working in music. I wasn’t actually “working”. Rather, I dropped out of university to volunteer at murderecords, an artist-owned label in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

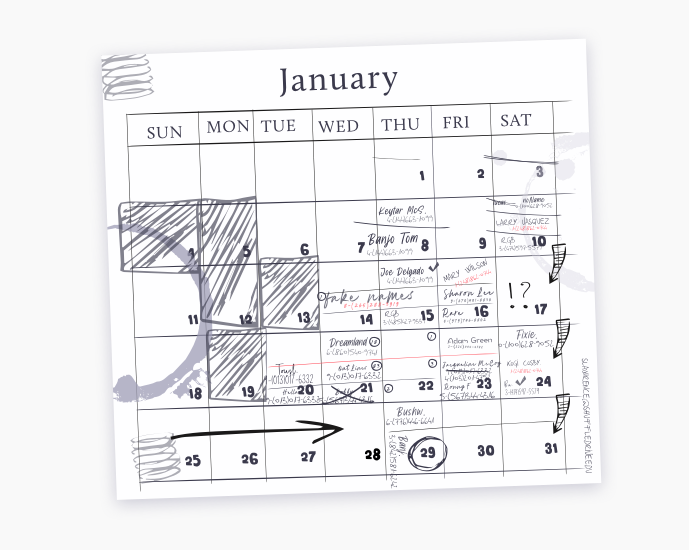

After sorting out the mail order for a few months, my first proper task was booking tours. The mid-nineties were a lot like it is today. It was nearly impossible to get a booking agent until you don’t really need one anymore. I am exaggerating of course, though that adage still rings true. I expect the tour booking process is still much the same. Though of course, as I write this, absolutely no one is currently touring. The process is simple. The first step is to contact clubs along a route that makes sense and hope that a booker in each town wants the artist to play. Of course, a booker will generally have never heard of a completely new artist. If so there is another step, convincing the booker why the artist is worth their attention.

I remember enjoying booking shows, especially if they actually ended up happening and went well. Halifax sits on Canada’s east coast so bands always had a long drive to get to the bigger markets in Central Canada. Normally the first big gig would be Montreal, a 15-20 hour drive away. However, I realised early on that Montreal clubs worked under a very different system, Pay to Play.

The pay-to-play model

Normally an artist’s first show in any new city is tough. To get the gig one needs to play for a low guarantee (fee), a percentage of the door (no fee) or no promise of anything whatsoever. Montreal was different though, club owners actually wanted artists to pay them to play gigs.

This is a long time ago but I don’t remember thinking that was a good idea, even back then. It seemed super shady to me, while also being counterproductive. I felt bands should be get the gig by virtue of the promoter feeling they would be a good draw. That they would be booked because they liked them or that they felt the audience would, or both.

This wasn’t the system for all artists and all venues, so why was it the case in Montreal? I am still not completely sure. What I do know though is that it is rare for anyone to make money on those first few gigs. It is about relationship building. Clubs and bookers need to have confidence the artist will draw an audience. Artists and their booking agents need to be sure promoters are reliable. They would also be expected to properly supporting future shows including a decent guarantee and good promotion.

Performing Ideas: Pay-to-play in tech

Conferences are like the tech world’s gigs, a performance of ideas instead of music. I never really liked conferences until I started doing more of them pre-Covid. Recently I was thinking about how many interesting people I’ve ended up working with just from going to Tallinn Music Week in 2019.

Much like gigs, there are more people looking to share their ideas than can be accommodated by fireside chats, panels or workshops. To get the gig in tech, conferences seem to book what is trendy, instead of current. Likewise they tend to look for “big” names, instead of ideas. It seems that those are natural challenges everyone is trying to overcome. In the same way promoters don’t only book artists they like, a packed-out gig is the number one priority. Building a successful conference is the same.

I was however surprised to read recently that one conference was offering seats on panels in exchange for advertising money. I understand, even appreciate, the idea of a sponsored panel. Getting a company’s message across in a focused way, openly and clearly sponsored, can be effective. However, the idea of panellists paying to be placed on panels, either directly or indirectly, is of concern to me.

Perhaps I am being naive here, but this approach had never really even crossed my mind before. Here is yet another example of how music and tech operate in similar ways. As pay-to-play is both shady and counterproductive for artists, conferences charging panellists to speak is shady and counterproductive for start-ups.

At their best, conferences are an exchange and evaluation of new ideas. Much like pay-to-play being bad for artists it is bad for panellists. It devalues their ideas by attaching a price tag to them. It is also bad for the audience because they can not objectively evaluate the context, validity and motivation behind the ideas being presented.

So what it the result?

Another clear sign this is not a practice any artist or start-up will want to take part in is that it only happens when they are just starting out. Artists get paid more and more money for gigs the larger their audience becomes. As speakers deliver more innovative and effective ideas they too are paid higher and higher speaking fees.

Buying a place on stage or a seat at the table doesn’t fast-track your art or your message. In fact, it does the opposite. A venue or conference’s reputation is also at risk. An audience is paying money on the expectation they are seeing and hearing what the agent or curator believes is most relevant to their audience or what should become most relevant. Pay-to-play destroys that trust.

The fundamental reason why I have never understood the idea of pay-to-play is that it pollutes art with commerce. As an artist or speaker, the value of your art or ideas needs to be assessed objectively in order to be taken seriously. Bad ideas should be brought into question, challenged and dismissed. Or simply ignored, just like no one listens to bad music.